This post isn’t going to be a cheery travel post, but anyone who follows me here or on Instagram will know that part of the reason I travel is to learn more about the histories of countries, and more often than not that includes difficult, incomprehensible stories – which are so important we have to read them and re-tell them.

So let’s visit Patarei. Paterei Prison lies about a 30 minute walk out of central Tallinn, and is the next installment from the Estonian leg of my Baltics road trip. It is really worth a visit if you get the chance while in the city.

The prison was actually built as a fort in the 1830s by the Russians when Estonia was part of the Russian Empire. When the Russians were defeated in the Crimean War, the fort was converted in to barracks. When Estonia gained independence (for the first time) in 1918, the site was reconstructed as a prison.

It remained a prison until 2005. Yes, 2005.

From 1940-1991, Estonia was part of the Soviet Union (USSR), and ‘behind the Iron curtain’. This means it didn’t have independence and the prison was under Soviet control. For Estonians, Paterei is one of the most prominent symbols of Soviet terror.

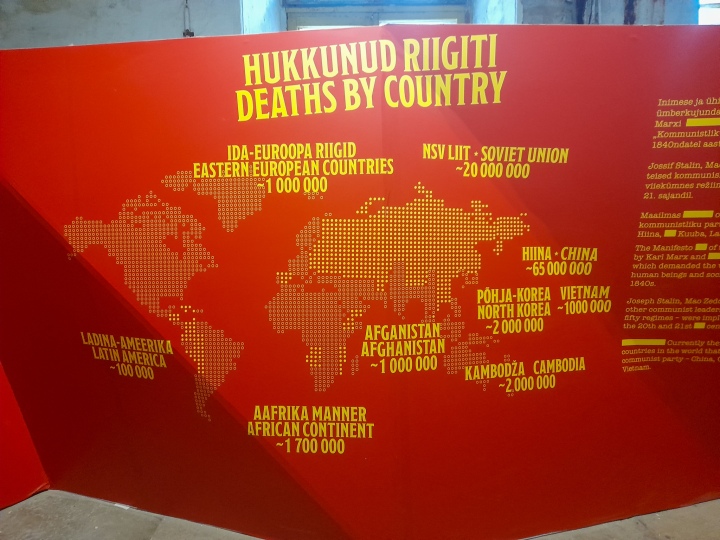

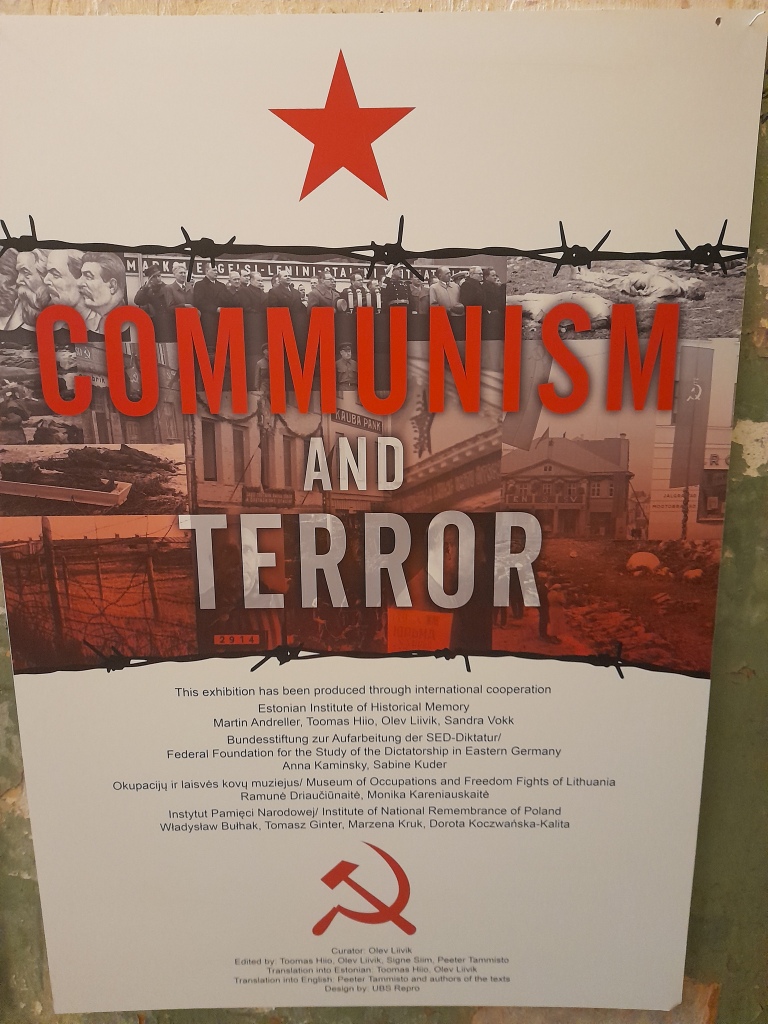

In 2018, the site was opened to the public with an exhibition telling the story of Communism and the Soviet regime’s atrocities here in Estonia during the years of Soviet rule. In 2025, the museum is expected to be expanded to address communism more widely and include exhibits on Cuba, China, Cambodia and other areas where human lives have been lost as a result of a Communist regime.

Visiting the museum is sobering. At the time of my visit it wasn’t renovated, so you literally walk around the prison as it was left at the end of its life. There are a lot of boards in each of the cells and areas though, so reading it all takes at least a few hours.

The first cell blocks tell the story of individual prisoners held there. There’s the story of the farmers who refused to give up their crops to the Communist regime (under Communism, everything you produce is for everyone else so you contribute it to the main ‘pot’) and were tortured and shot, or sent to Siberia, just for refusing. In the end 75% of Estonia’s farmers were killed, sent to labour camps or deported so that those left were favourable to the regime.

There’s the story of the ex-leaders of the Estonian Republic – all of them bar 1 (who escaped to Sweden in 1940) – were murdered by 1944 following torture. For one of them, he was picked up from his home and just disappeared with his wife never seeing him again and never finding out what happened to him before she died.

There’s the story of the teachers who continued to use Estonian as the language in their classes, rather than Russian – they were tortured and killed for being enemies of Communism. There’s the native Germans living in Estonia, now enemies of the state in the war. There’s the Gypsies who were socially ‘undesirable’, the University student who defaced a Stalin poster, the father who has been informed on because the next door neighbour wants to steal his wife.

There are every day people, going about their lives. Abducted, sent to labour camps, tortured, shot, sent to Siberia, fed to dogs, tossed in to mass burial pits. In the end Estonia lost 25% of its population. Just think about that – 1 in 4 people you know just disappearing, in the course of just a few years, for often completely trivial ‘crimes’.

After the individual stories, there is also a gallery about the wider impact of Communism – what does the ideology mean, where did it come from, how did it get a foot in the door. There is then a great exhibition of Communism during the post-WW2 period (in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Budapest and various other countries).

It tells the story of resistance, of bravery, and ultimately of death because these people were more often than not murdered in cold blood. There are distressing pictures – one of the resistant fighter alive and smiling, and one of the fighter dead. The most upsetting one was of a 17 year old who threw paint at a Communist monument. Tortured and left dead in the street.

After that harrowing gallery, there’s an ‘honour board’ (Soviet honours) of the guards and controllers who ordered atrocities such as murders and deportations. What I found hardest here is that after the Soviet Union fell, these people didn’t go to Russia – they stayed in Estonia, living side by side with the people they’d once treated as no more than vermin. One of the main organisers of a 1969 deportation and mass murder for example, lived in Tallinn until his death in 2000, well after the 1991 fall of the USSR.

It made me realise that even once Estonia had independence in 1991, it wasn’t overnight. The transition must have been so hard – no infrastructure set up, no teaching agendas, no funding, nothing. And for the people to adjust to it as well must have been a real challenge.

After these exhibitions you can also visit the bathrooms (they are awful), torture rooms, solitary confinement rooms and guard’s rooms. In the torture room it tells the story of a woman arrested for being related to someone in political opposition to the Communist regime – she was tortured for days whilst pregnant, and when she gave birth prematurely they took her baby and she never saw it again or even knew if it survived. She was also left infertile from the torture.

I think it’s safe to say this museum is not an easy visit. It’s not Tallinn’s beautiful romantic old town. But it is so important we share these stories, and understand the context as well behind current feeling in the region around Russia and the war in Ukraine.

What do you think? I appreciate this wasn’t a fun post, but I hope it was interesting and informative none the less. Thank you for reading. Stay safe and happy travelling.

Leave a comment